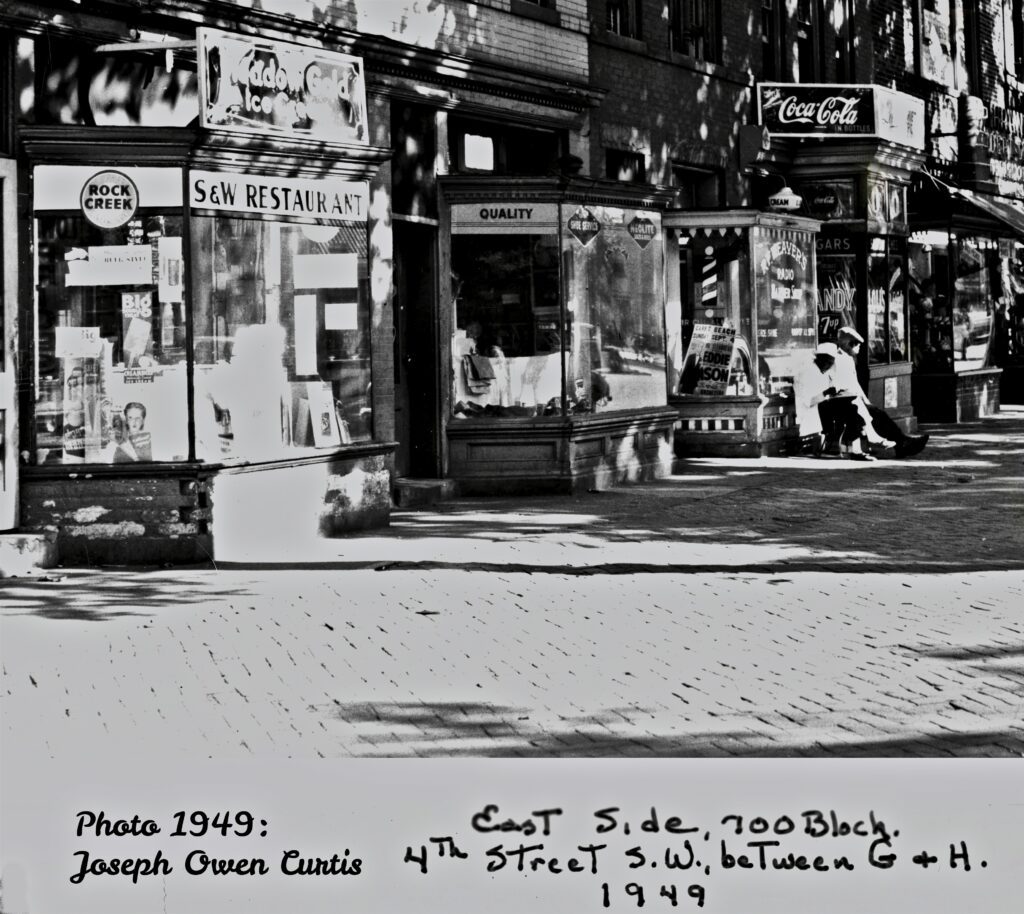

Joseph Curtis took this photo in 1949 of a group of shops on 4th Street, SW, including the former site of Frank’s Department store, across the street from current-day Amidon-Bowen Elementary School. The owner of Frank’s sued the government because it deemed the area “blighted” at the time this photo was taken and therefore slated for destruction. The Supreme Court ruled against him in 1954, paving the way for Urban Renewal and the demolition of Southwest and thousands of other communities across the country.

By Carolyn Swope

In the 1950s and 1960s, urban renewal in Southwest DC displaced around 23,000 residents. While we can easily see how Southwest’s built environment changed, it is harder to know what happened to the people who were forced to leave. A rich and valuable source of insight is available in the 1966 study “Where Are They Now?,” led by social work researcher Daniel Thursz. The findings suggest several main takeaways about post-displacement outcomes. First, the community was geographically shattered, with residents scattered “as leaves on a windy autumn day.” Second, residents generally did not move to wealthy and well-resourced neighborhoods, but to neighborhoods that would experience increasing segregation and disinvestment. Third, while residents’ housing quality indeed improved, their social and economic well-being did not, and they keenly felt the loss of their community ties.

How the Report Came to Be

The DC Health and Welfare Council contracted with the Redevelopment Land Agency (the government agency in charge of DC urban renewal) to operate a demonstration program offering services for relocated residents. The 198 participating families had not moved out of Southwest yet by 1959 and lived in Area C – part of the urban renewal project west of 4th Street. 80% were non-white and 88% were low-income. In “Where Are They Now?,” Thursz conducted a study of outcomes for 96 of these families five years after displacement. He was interested in testing two hypotheses: 1) that “evicted slum dwellers create new slums where they move, or at best move into other slums,” and 2) that “the grief due to a lost home and community lingers for many years, and that social fabric once destroyed is not replaced in five years.”

Where Did They Go?

The families studied lived scattered across 37 different census tracts. Families who were not living in public housing were often the only family from the sample in their neighborhood. Yet despite this wide dispersal, Thursz pointedly noted, not one household had moved west of Rock Creek Park – “a section of Washington which is inhabited by middle and upper class families and which is still almost entirely white.”

- 23% moved to the Southeast quadrant east of the Anacostia River

- 19% moved to Southeast on the north/west side of the Anacostia River

- 19% moved to Northeast, mostly east of the Anacostia River

- 8% moved to Northwest

- Over one-quarter remained in Southwest, almost all in public housing

Housing Conditions

The study did find that residents’ housing conditions had markedly improved. Before urban renewal, almost half of families lived in dwellings which needed major repairs or were deemed dilapidated and unfit for use. Afterwards, not a single family in the sample did. Likewise, only 22% of former homes had been considered in good condition; 86% of new homes were. The proportion of homes equipped with basic amenities dramatically increased:

- 97% of homes had flush toilets (43% of dwellings pre-urban renewal only had outside toilets)

- 94% had central heating (over 70% previously lacked it)

- 96% had bathrooms with running water (44% formerly lacked baths)

- Every home had electricity (one in five previously lacked it)

Residents themselves also generally perceived their new homes as better-quality. 50% reported that they liked their new dwelling “very much more,” and another 14% “somewhat more,” relative to their previous Southwest dwelling, while only 12% disliked their new home in comparison. A majority indicated greater satisfaction with outside appearance, bath or toilet facilities, heating system, kitchen facilities, sleeping space, and ease of cleaning – although a substantial contingent for each of these factors (8 to 15%) actually found their new homes less satisfactory, and residents who felt their new homes were more satisfactory with regard to yard space and room for children to play were in a minority.

However, Thursz also noted that 57% of surveyed residents said they were paying more for housing than they had previously paid in Southwest. The increase was often substantial: of these residents, 60% reported paying at least $20 more per month (around $200 in 2024 dollars), and 15% reported paying over $40 more per month (around $400 in 2024 dollars). He concluded that “a good part of the cost for the improvement in the physical surroundings of the relocated families is being borne by the families themselves.”

Social and Economic Outcomes

In contrast, outcomes related to work, health, and community were worse after displacement. A higher proportion of heads of households were now not working – 62%, compared to 52% before. Residents explained that they now lived farther from the workplace, adding difficulties of navigating distance and affording transportation. One woman explained that her husband had become “‘sick from grief’” at having to lose his home, business, and friends,” contributing to his unemployment. Further, only around a quarter of working respondents earned more than when they lived in Southwest, while 18% now earned less. 50% reported having more money worries.

Before relocation, 41% of heads of households reported that illness had a serious effect on their family. Although urban renewal was justified in large part on public health grounds, and although residents’ housing quality had indeed improved, it had not resulted in any improvement to these residents’ health: A slightly higher proportion, 43%, felt illness or disability had seriously affected their family since leaving.

Residents had had strong community ties in Southwest – most had lived there for more than 10 years – which were not replicated in their new neighborhoods. 63% reported no knowledge at all of any neighborhood or block clubs; 60% were unaware of any settlement house, community center, or social agency where they might turn for help in their new community. Only 27% felt that there was “more neighborhood feeling” compared to Southwest, while 42% disagreed. And only 19% felt that people who lived in their new neighborhood were better neighbors, while 41% disagreed. Perhaps most strikingly, more than a quarter of residents reported that they had not made even one new friend in their neighborhood after five years.

Public vs. Private Housing

Compared to residents moving into private-sector housing, Thursz found that “the public housing resident is a much more integrated, optimistic, and informed person.” Public housing residents reported lower levels of anomie, and much greater hopefulness about the future, feelings of belongingness in their neighborhood, belief in ability to organize and improve the neighborhood, and knowledge of agencies helping people in the community. For example, 67% of public housing residents felt that things would get better for them and their family, while only 38% of private housing residents felt that way. Further, public housing residents were much happier that they had to move (55% reported being happy, compared to 32% among private-sector residents) and more likely to feel that the government was “right in changing Southwest” (78% agreed, compared to 54% of their counterparts). These findings are particularly important because urban renewal intentionally and explicitly prioritized the private sector. They suggest that public housing was a more promising avenue to improve outcomes for low-income residents – if such improvement had really been a goal of the program.

Conclusion

Although planners and redevelopment officials usually spoke as if it did not matter where Southwest residents moved and focused solely on the physical quality of the individual housing unit, Southwest residents had strong ties and connections to their community which were also important, and the disruption from their rupture was deeply harmful. In the documentary Southwest Remembered, Thursz reflected, “They were not living in slums. They were living in good, adequate housing. Many of the problems that they had suffered from were gone.” However, “In the process of moving them from Southwest, we had destroyed something which was even more important to them – namely, the sense of community, the friendships, the support, that existed in a rat-infested slum. We had forgotten that this was home to these people.”

“Where Are They Now?” is publicly available online for anyone interested in reading it in full.