By Southwester Staff

With cherry blossom season in full swing, the museums of the Smithsonian are showcasing Japanese art from the 13th to the 19th centuries.

In early March, the Freer Gallery launched a new exhibition showcasing the full scope of the museum’s medieval Zen collections, one of the broadest in the world, for the first time since the museum’s founding.

Mind Over Matter: Zen in Medieval Japan includes rare works illustrating the visual, spiritual, and philosophical power of Zen and its roots in the culture of medieval Japan. Monastic Zen painting in medieval Japan featured paintings in monochrome ink, often by Zen monks, which have influenced artists and formed a thematic backbone of Japanese art and cultural identity. The exhibition will be on view through July 24, 2022.

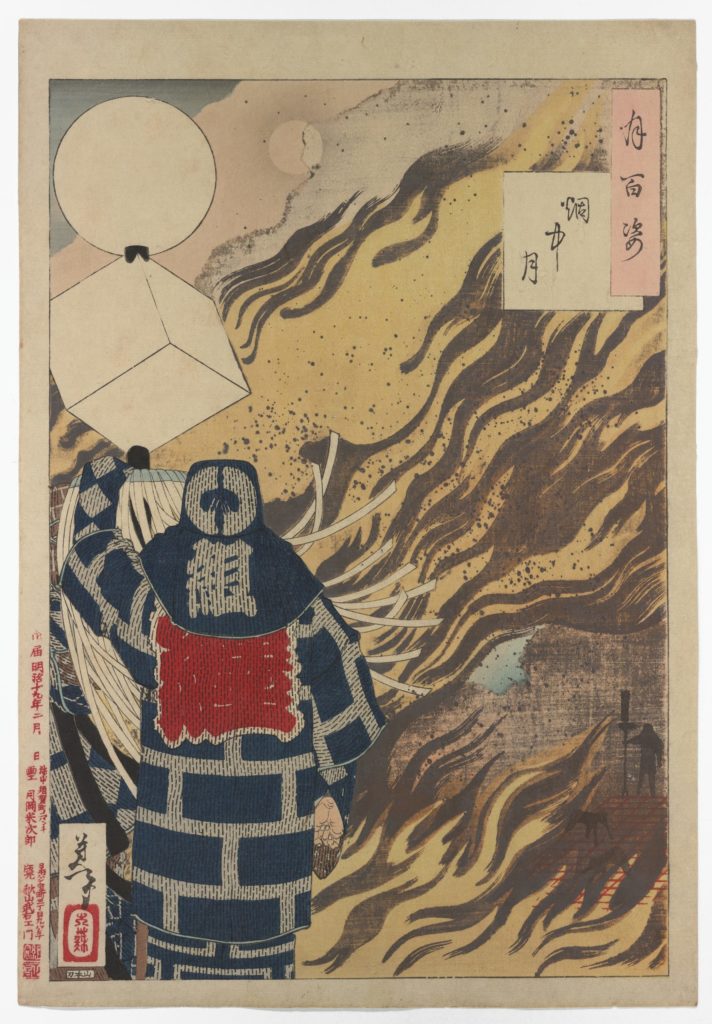

Also in March, the National Museum of Asian Art debuted a new exhibition of Japanese prints. The exhibition, Underdogs and Antiheroes: Japanese Prints from the Moskowitz Collection, features stories and legends of individuals who lived on the fringes of society in early modern Japan.

“Over the course of Japanese history, the stories of countless underdogs and antiheroes have inspired a deep affection for narratives of the downtrodden in the arts,” Kit Brooks, Japan Foundation Assistant Curator of Japanese Art said in a press release. “This was especially true during the early modern period, when members of the urban commoner class tried to assert themselves against the ruling samurai by creating a distinctive culture of their own.”

Prints in the exhibition spotlight virtuous bandits, sumo wrestlers and rogues from the kabuki theater. From scenes of tattooed firemen brawling with rival groups to those of sumo wrestlers enjoying a feast under cherry blossom trees, the exhibition features subjects that are not commonly associated with traditional Japanese print culture but were nevertheless central to the interests of an early modern public. Sumo wrestlers were celebrated and respected even though they lived outside of the traditional class system. Like other ancient rituals, sumo first appears in one of Japan’s national epics, the eighth-century Kojiki, and evolved into a national sport. Its popularity peaked in the late 18th century, eventually eclipsing even that of kabuki theater, the early modern period’s most influential form of entertainment.

“Identifying the struggles of unconventional heroes who prevailed against all odds, townspeople embraced both old legends and new ones,” Frank Feltens, Japan Foundation Associate Curator of Japanese Art said in a press release. “These stories were immensely popular, which enabled savvy publishers, artists and printers to cater to fans hungry for images of these figures.”

The exhibition will be on display through January 29, 2023.