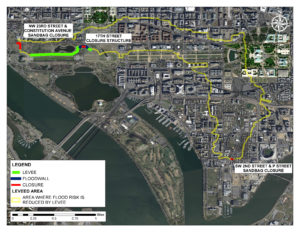

Location of the D.C. levee system and leveed area; Photo: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

The District of Columbia Levee System, also referred to as the Potomac Park Levee System, was constructed near the National Mall by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) in the 1930s to reduce Potomac River flooding to Southwest D.C., the Federal Triangle and other areas west of the Capitol. Operated and maintained by the National Park Service (NPS), this levee system has been protecting Southwest from severe flooding for nearly a century.

On Oct. 30, USACE and NPS hosted a public meeting at Westminster Presbyterian Church to share information with attendees on the results of a safety risk assessment completed for the District of Columbia Levee System. DC Homeland Security and Emergency Management Agency (HSEMA) also presented on flood preparedness measures for property and business owners/renters and evacuation procedures.

“The purpose of this meeting was to improve the public’s understanding of flood risk in the area as well as to educate residents and businesses on steps they can take to prepare for and reduce damages from flooding,” said Jehu Johnson, USACE, Baltimore District, Levee Safety Program manager. “Managing flood risk is a shared responsibility—from the federal level to the public. Residents in Southwest D.C. benefit from this levee being here, but they would also be the ones impacted if a severe storm were to bring water over the top of the levee and cause it to break due to pressure or erosion, as the area naturally sits on lower ground.”

This meeting was held as part of a nationwide effort USACE is leading to individually assess levees across the nation to determine their safety risks and present this information to the public.

“In analyzing these risks, the Corps not only looks at the condition of the levee system, but also considers how often the area may flood and the population and development at risk behind the levee system,” said Johnson.

“The [D.C.] levee system is well maintained and in good condition,” said Mark Baker, NPS dam and levee safety officer. “It is designed to hold back major Potomac River floods; however, a stronger storm could cause water to come over the levee system and break the levee, and the consequences could be catastrophic. We also have to consider the three open areas across roads that may need to be closed off by sandbags or aluminum panels, like across 17th Street, prior to a large flood; the volume of tourists in the area; and the complexities associated with evacuation planning.”

The District of Columbia, including Southwest D.C., can be flooded three ways: Potomac River freshwater flooding from the upper watershed, Potomac River tidal/storm surge flooding (including during a hurricane) and interior/stormwater flooding. The levee system reduces risks from freshwater and storm surge flooding. The last major riverine flood occurred in 1996, and the last major tidal flood occurred during Hurricane Isabel in 2003.

It is estimated that the levee system reduces the risk for a flood that has between a 0.2 and 0.1 percent chance of occurring in a year. A 0.2 percent chance equates to a 1 in 500 chance of occurring in a year. A 0.1 percent chance equates to a 1 in 1,000 chance of occurring in a year.

“Communicating flood risk is hard,” said Johnson. “We use the best modeling available that incorporates historical gauge data to determine these probabilities. It is a moving target. We prefer to communicate using the percent chance a flood has of occurring in a year rather than a certain-year flood event, for instance. A flood deemed a 1 percent annual chance flood or 100-year flood can happen twice or more in one year, and what was a 100-year flood ten years ago will not be the same as the 100-year flood of the future. We can just look to Ellicott City, Maryland, that received two estimated 1,000-year storms less than two years apart. Across the nation, we are experiencing stronger storms more often.”

Though the levee system reduces risk from major flooding along the Potomac River, there still remains the threat of interior flooding, which is caused by heavy localized rainfall that falls directly over the District in a short period of time and overwhelms stormwater systems, like what was experienced in 2006. Even if residents are not likely to be affected by river flooding, it is likely they will be impacted by interior flooding.

“There is little warning time for an interior flood, which is why taking steps now to reduce flood risk is so important; flooding from the river provides a longer warning timeframe,” said Donte Lucas, DC HSEMA Deputy Chief of Operations. “Steps anyone can take to reduce flood damage include purchasing flood insurance even when not required; moving valuables and utilities to higher levels; sealing cracks; being aware of individual flood depths and risk at home and work; signing up for emergency alerts like AlertDC; creating an emergency kit; and knowing evacuation procedures. If you have enough warning for a Potomac River flood and can do so safely, it’s also a good idea to move your car to higher ground if it is parked outside.”

The area behind the levee contains more than 40,000 people and $14 billion in property, including assets and infrastructure of national importance, such as congressional offices, national monuments, the Smithsonian, the National Gallery of Art and the Metro subway system. If the levee were to overtop with water and break during a severe Potomac River flood, flood depths in certain areas of Southwest D.C. could be greater than 15 feet.

“This is a complicated issue, and we’re doing the best we can together to continually assess our flood risk in D.C. and determine ways to lower that risk,” said Baker. “Federal partners held two workshops this summer to discuss ways to reduce the threat of interior flooding; the Army Corps is looking into increasing the height of the D.C. Levee System; and the Park Service is investigating the use of temporary barriers to be deployed prior to a strong storm to add an extra layer of flood risk management for D.C. We have to be prepared for the worst because there is a lot at stake.”

For links to the presentation and handouts from the meeting, go to https://silverjackets.nfrmp.us/State-Teams/Washington-DC. You can also plug in your address and manipulate various flood depths to see when you may flood at your location through an online tool known as the Anacostia and Potomac River Flood Inundation Mapping tool, found at https://www.weather.gov/lwx//PotomacInundationMaps. Finally, sign up for AlertDC at http://alertdc.dc.gov.

By Sarah Lazo, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Baltimore District