Part 1 of a 2-Part Series on the Digital Divide

By Grace Hu, parent at Amidon-Bowen Elementary and parent lead for Digital Equity in DC Education

When I joined the Amidon-Bowen Elementary PTA in 2016, I never dreamed that four years later I would be leading a coalition of parents to push the city to close the digital divide—the gap between those who are able to effectively access and use technology and those who are not. Nor could I have predicted that a pandemic would worsen existing inequities by limiting physical access to education and critical services that are increasingly based on internet access. More than 160,000 DC residents, including thousands in Southwest DC, lack high-speed home Internet service and are being left behind due to a problem that is fixable, if only our leaders would prioritize fixing it.

Residents Left Behind

Even before the pandemic, residents needed reliable access to high-speed internet (broadband), computer literacy skills, and a computer device to fully participate in education, the economy, and civic life. Much of DC Public School (DCPS) curriculum, testing, and remediation programs are now online. Applying to jobs, city services, and maintaining many connections with our neighborhood, friends, and family are done online. Many independent reports show that high-speed internet access has a direct impact on jobs and the economy.

Despite this increasing reliance on technology, 1 in 4 DC residents, including many in Southwest DC, lack high-speed home Internet service. Nationally, 25% of black teens report trouble completing homework due to lack of a reliable computer or Internet connection. Even when internet service is available at home, it may only exist through a cellular data plan that may have monthly usage limits and be prohibitively expensive to maintain or expand. Sharing such a limited internet connection among many family members puts an even greater strain on those families who now have to, for example, decide whether to cut off a video call for work or for school.

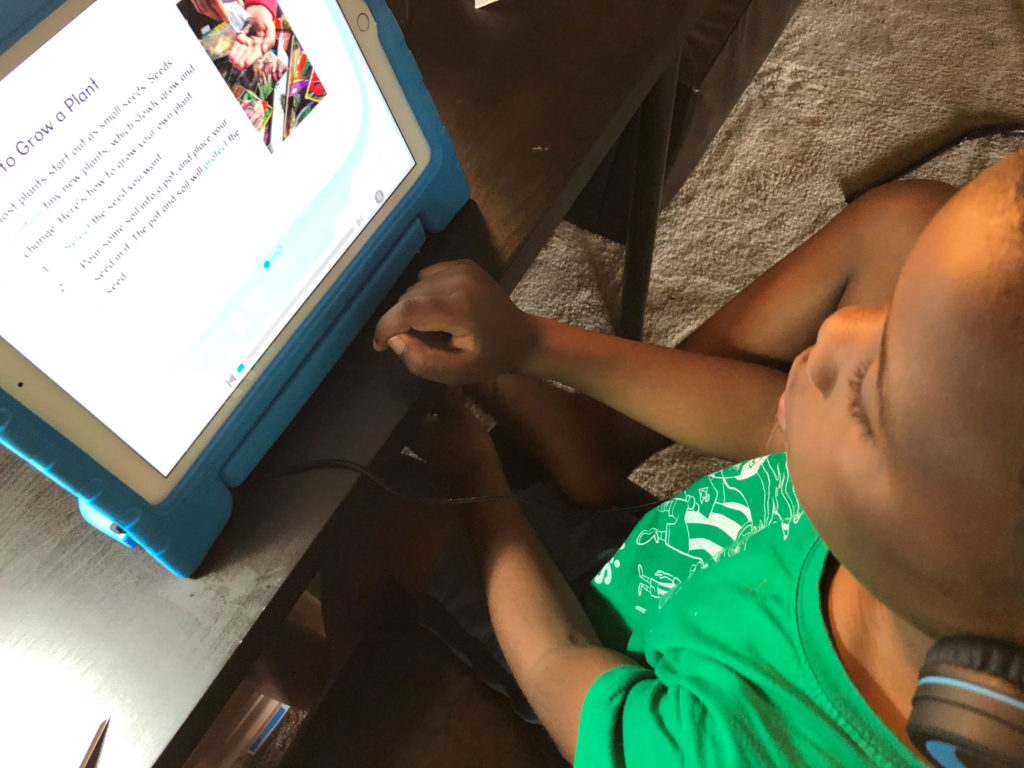

The digital divide impacts both the young and old in our community, especially during this pandemic. Students have been expected to complete online learning and attend virtual class meetings. Children as young as five may be the only family members who can try to navigate websites if others in their family are illiterate, non-native English speakers, or unfamiliar with technology. While DCPS has loaned out laptops and hotspots to some students, many of those will need to be returned and serve only as a stopgap measure. Summer programming for children is expected to occur online, with the city’s website stating that registration must be completed on a computer, not a phone or tablet. Meanwhile, seniors without technology are unable to access virtual church services and community functions that have moved online during this public health emergency. For seniors, maintaining the social connections that are vital to their health and well-being can be much harder now that they are dependent on unfamiliar devices and online tools.

In the midst of these challenges, volunteer organizations have stepped up. Since 2008, the Southwest Neighborhood Assembly (SWNA) has collected and supplied computers to families and offered computer training for seniors and students. During the pandemic, Serve Your City, which manages the Ward 6 Mutual Aid Team, has collected used computers and distributed them to residents. While helpful and needed, these volunteer-led efforts are limited in scope (reaching at most hundreds at a time) and usually are focused on providing computer hardware rather than Internet access. Unfortunately, we cannot close the digital divide, either in Southwest or the city in general, by relying solely on the volunteer work and generosity of neighbors. To close the digital divide, the DC government must step up.

City Leaders Need To Step Up

The role of city government in solving the digital divide is especially pertinent during a year in which several Council positions are up for election. The DC Council plays a critical role in holding the mayor and executive branch accountable, and for funding city government. On May 18, I participated in an online discussion on the digital divide with Markus Batchelor, current Vice President of the State Board of Education and candidate for At-Large Council position. Batchelor, who grew up and still lives in Congress Heights in Ward 8, recognizes the urgency of closing the digital divide and said: “It’s going to take bold investment for improving Internet connection, expanding municipal Wi-Fi, and making sure that we have technology for every student.”

Vice President of State Board of Education, speaking to residents

before the pandemic; Courtesy of Author

Batchelor also discussed the need for city leaders to provide oversight, stating “there was money put in the [mayor’s] budget to help upgrade units across our public housing communities, and we need to make sure there’s oversight from the Council to make sure there is money invested in upgrading the technology systems in those public housing units.” He stated that city leaders should “intentionally target” senior communities, senior centers, and seniors at home for the provision of technology and computer literacy training. “We’ve got to think about this from different angles with the goal of making sure that everyone, no matter your traditional station or barrier in life, has that access.”

DC government has tried to address the digital divide for many years, but its efforts have fallen short of providing technology access for all residents. In 2010, DC used more than $17 million from the federal government to build out broadband infrastructure to provide Wi-Fi for DC government agencies and community institutions such as schools, libraries, and senior centers. However, DC did not build out “last mile” service to neighborhoods, opting instead to rely on internet providers such as Comcast to provide services to residents for a monthly fee. DC also created an office, Connect.DC, to lead outreach and computer training efforts to lower-income residents who lack both computer hardware and Internet. Connect.DC’s funding has been stagnant the past few years and is significantly reduced in the mayor’s FY21 budget, from $1 million in FY20 to less than 400,000 in FY21. The small scale of these efforts means that, if the current lack of priority persists, we will not close the digital divide for years to come.

Other cities, such as Seattle and Chattanooga, have prioritized technology access for their residents and have funded everything from library hotspot loan programs and grants for local digital equity projects to free Wi-Fi on buses and in public housing, and publicly-owned networks designed to keep the Internet affordable.

How You Can Help

With DC Council budget hearings coming up, Southwest residents have the opportunity to urge city leaders to make investments to close the digital divide. The currently proposed Mayor’s budget underfunds the DCPS technology needed to support both in-school and at-home learning and includes no additional funding to support expansion of Internet access or computer literacy training. Here’s what you can do:

- E-mail or submit written testimony to the DC Council on the digital divide. E-mail digitalequitydc@gmail.com for details.

- Tell us your story of how the digital divide has impacted you, your family, or your community. We will use these stories to write part 2 of this Southwester series on the digital divide. E-mail digitalequitydc@gmail.com or leave a voicemail at 202-556-1610 to set up an interview to tell your story.

- Stay informed on the advocacy efforts of our parent group, Digital Equity in DC Education, by following us on twitter at @DigitalEquityDC.